Interview with Tobias Sick

Interview with Tobias Sick

Would you briefly introduce yourself?

My name is Tobias Sick and I am currently working as a research associate at the Institute of Arabic and Islamic Studies at the University of Münster, where I am also pursuing my dissertation project. My thesis focuses on Ottoman Turkish (and other) translations of Persian advice literature that were produced in the early modern Ottoman Empire. I obtained my BA and MA degrees in Languages, History and Cultures of the Middle East from the University of Tübingen, and my main fields of interest pertain to the history of multilingualism and translation in the early modern Islamic world, manuscript culture, and Persian literature in a more general fashion.

What are you currently working on?

My research focuses on the so-called Pandnāma-yi ʿAṭṭār (ʿAṭṭār’s Book of Wise Counsel), a pseudo-ʿAṭṭārian work of Persian advice literature which was particularly popular in the Ottoman realm and was thus translated and commented upon numerous times in Ottoman Turkish during the early modern period. These Ottoman Turkish verse and prose renditions of the Pandnāma form the primary focus of my thesis, where I attempt to analyse and contextualise them from both a philological and a translatological perspective.

Currently, my research centres on several themes which do not as often feature prominently in the current literature, despite their prevalence and relevance for studies of premodern translations and their reception. For instance, the topic of interlinear translation (i.e. between the lines of the original) is of great importance to understanding the transmission and reception of the Pandnāma and other works; yet, it is somewhat challenging methodologically, due to its ad-hoc nature and the predominant absence of proper attributions in terms of authorship. Another important aspect of my research is the role of multilingualism in the reception of such works more generally, which is another important aspect of my research. In this regard, it is especially the continued juxtaposition of – in my case – the Persian original and the Turkish or Arabic rendition within translation works, translation manuscripts, and libraries that is a key element in understanding how literary translations were read and used in, for example, didactical contexts. For the Pandnāma, it is this context of reception which is the most prominent in the early modern Ottoman Empire and beyond.

Of course, there are many more aspects one could discuss. Ultimately, however, I am wrapping up my discussions of these and other topics within the dissertation and preparing to finalise everything in the coming months in so that I can submit in late spring of the next year (2025).

Why did you apply to the Andreas Tietze Memorial Fellowship?

My main motivation for applying to the Andreas Tietze Memorial Fellowship was to consult a number of manuscripts relevant to my dissertation project, which are hosted in several libraries located in Vienna. Furthermore, I wished to visit the Department of Near Eastern Studies in Vienna and meet with both researchers and students there to get a grasp of the landscape of Ottoman and Turkish Studies in Austria. Since Vienna and, particularly, the Department of Near Eastern Studies is renowned for its contributions to the fields of Ottoman and Turkish Studies, I wanted to get in touch with scholars conducting research there. Lastly, I also wanted to see and explore the city of Vienna and the many cultural sites connected to Austrian and Ottoman history, since I had never been there before.

How did the fellowship contribute to your research?

During the fellowship period, I was able to consult numerous manuscripts held in institutions such as the Austrian National Library, the National Archives of Austria, and the Library of the Mekhitarist Congregation in Vienna. These manuscripts consisted of copies of the original Pandnāma, both interlinear and substitutive translations of it, commentaries, and a few other works relevant to my study. Spending time reading, making notes, and taking some pictures of these materials was the most important part of my stay, and luckily, I was able to see all the materials necessary for my thesis.

Among these, there were many interesting copies pertaining to works such as the verse translation of the Pandnāma attributed to the poet-translator Edirneli Emrī (d. 983/1575) or the Saʿādetnāme (Book of Felicity), a prose commentary by the famous mas̱navī commentator Şemʿī (d.1011/1602-1603). I also came across a copy of an Ottoman-Turkish translation which, according to the ex libris, belonged to the Austrian Orientalist Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall (d. 1856), who actually created a selection of German translations from the Persian work himself.

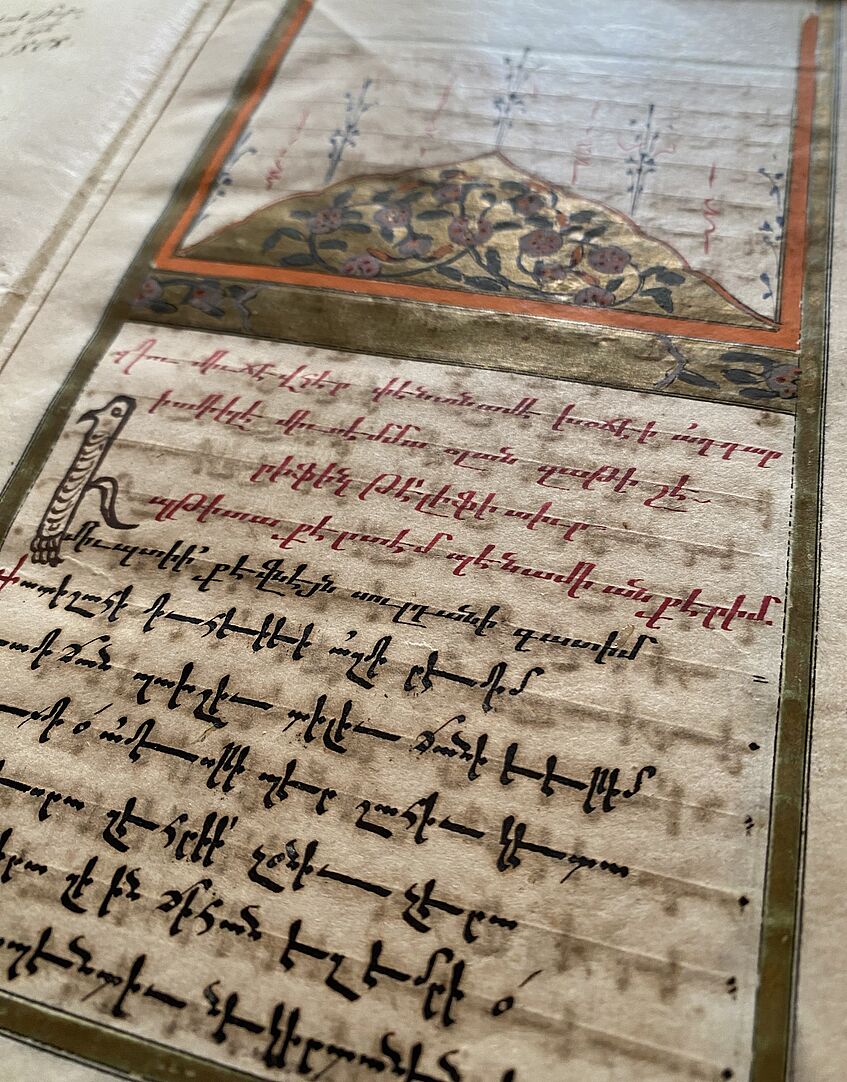

However, during this research stay, one manuscript was particularly important to me because, to my knowledge, it is the only textual witness to the reception of the Pandnāma in Armenoturkish. This work, upon closer examination, turned out to be an Armenoturkish rendition of the verse translation penned by Emrī (mentioned above) in the 16th century. In shedding more light on this work in this particular linguistic form of Turkish, both on the text and the copy itself as a material artifact, I hope to be able to get a better grasp of the multifaceted readership of the Persian original and its Turkish translations within and beyond the Ottoman realm. I was thus very happy to find the manuscript accessible in the Library of the Mekhitarist Congregation, thanks to the help of the librarian, Pater Simon.

Moreover, using the department’s well-equipped library, I was also able to consult Turkish secondary sources that were previously inaccessible to me. Through these sources, I established a comprehensive overview of the production and proliferation of lithographic and typeface print editions of Pandnāma translations, commentaries, as well as the Persian original in the Ottoman Empire during the 19th century – which has become quite an extensive list by now. This helped me to get a more complete understanding of the reception and relevance of (translated) Persian literature and its transformation through the introduction of print media in the region.

Do you want to publish or present your research to the academic community? How will it go further?

I have already presented some of the research I conducted during the fellowship at an academic workshop in early November 2024 in Istanbul, dealing with the paratextual evidence found in translation manuscripts, such as ownership notes or seals, to trace the contexts of their transmission and reception. During another workshop in January 2025, organised by the Emmy Noether Junior Research Group TRANSLAPT in Münster, titled “Empire in Translation: Perso-Arabic Knowledge and the Making of Early Modern Ottoman Civilisation”, I will also be presenting some of the insights that I have gained during my research stay in Vienna. In addition, I am currently preparing an abstract for the Turkologentag (organised by the Society of Turkic, Ottoman and Turkish Studies), which will take place in Mainz in September 2025, where I hope to discuss some of the visual aspects of Ottoman translation manuscripts. Of course, ultimately, my research as a whole will be published in the form of my dissertation, which will serve as the main format for publishing my research findings.

Finally, I would also like to express my deep gratitude to the Department of Near Eastern Studies for receiving this fellowship and, in particular, Yavuz Köse, Onur İnal, Ercan Akyol, and all the other wonderful colleagues there for the warm welcome and many pleasant discussions. Furthermore, I want to thank Pater Simon Bayan of the Mekhitarist Congregation in Vienna for granting me access to his library and for trusting me while handling the manuscripts sources.